The History of Idumuje-Ugboko

Introduction

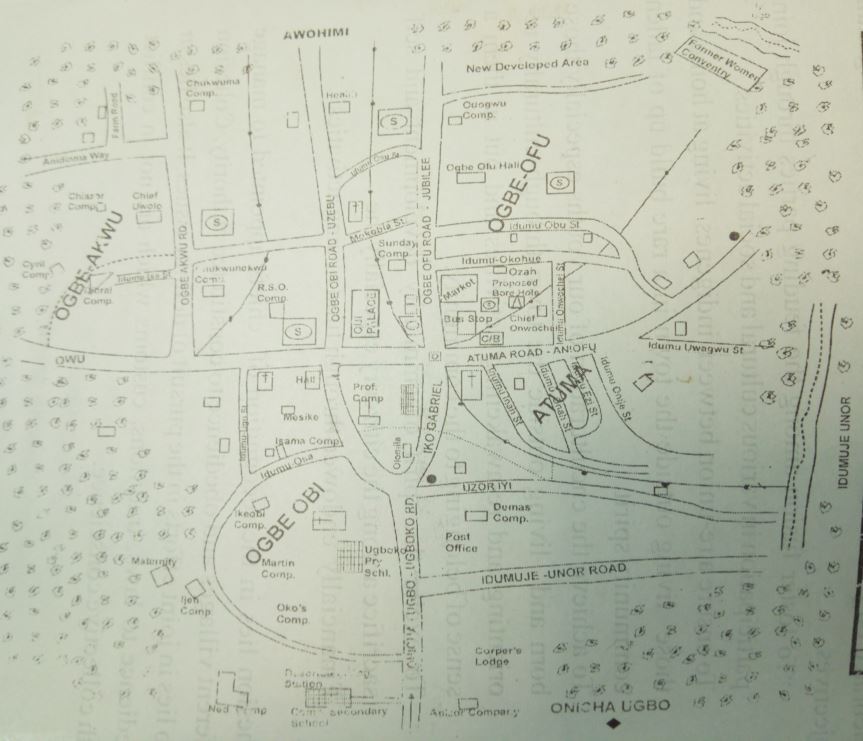

The rural town of Idumuje-Ugboko is situated in Aniocha North of Delta State, Nigeria. With a landmass of over nine square miles, and the geographic coordinates of 6° 21′ 0″ N, 6° 24′ 0″ E, it is bordered on the Eastern side by Idumuje-Unor; Onicha-Ugbo to the South; Igbodo to the West; to the North-East by Ohodua; Ewohimi to the North; and Epkon or Akpu to the North-West.

Unified under a hereditary monarchy, Idumuje-Ugboko is a close-knit, homogeneous group of four villages. The four villages whose founding fathers and the early settlers are reputed to have migrated from the various towns and kingdoms in, around, and beyond the present-day states of Delta and Edo are Atuma, Ogbe-Obi, Ogbe-Ofu, and Onicha-Ukwu. Unambiguously theists, the indigenous African religion was widely practised until the arrival of the Church Missionary Society (C.M.S.) changed the dynamics of their Pre-Christian belief system.

The Founding of Idumuje-Ugboko

Idumuje-Ugboko was founded in the 19th century by the descendants of Ogbeide, a Benin chief who, for unknown reasons, left Uzebu quarters an area in the old Benin kingdom and moved to Ahama, a town in the present-day Delta state. At some point, Ogbeide’s two sons, Aluya and Ologbo who may have migrated with him moved to Obior. Many years later, the two brothers with other migrants moved further East to Idumuje-Unor. Upon arrival at Idumuje-Unor, the migratory party settled in Ime Ogbe Isagbeme, a predominantly immigrant quarter. It is unclear if Onaifo, one of Ologbo’s sons was part of the migrant group that arrived at Idumuje-Unor from Obior or if he was born at Idumuje-Unor. What remains undisputed was Onaifo’s investiture as the Odogwu in Idumuje-Unor.

Meanwhile, as the need for new agricultural farmland grew, Nwoko, one of Onaifo’s sons moved further afield in search of unexploited agricultural farmland. Once he found an arable land, he wasted no time in erecting makeshift huts to shelter from the scorching sun and the torrential downpours, but he always went back to Idumuje-Unor, his home. When Onaifo died, Nwoko was a shoo-in to succeed him as the Odogwu in Idumuje-Unor. Despite the fact that he was backed by some elements within the immigrant community as well the locals, Obi Anyasi, the Obi of Idumuje-Unor demonstrated an unyielding determination in stopping Nwoko from succeeding his father. Instead, the Odogwu title was given to Nwoko’s paternal younger brother Igbenabor who was a very influential personage within the immigrant community.

Nwoko took this failure to heart. He was overcome by the feeling of embarrassment and ignominy. Unwilling to dwell on the setback or to hang around and feel sorry for himself, he sought permanent refuge in his distant farm, in a very thick forest. The self-imposed exile elicited sympathy and support from his siblings and a cross-section of the immigrant community in Idumuje-Unor. In a show of solidarity, a sizeable number of the immigrants decided to up sticks and pitch tenth with him in his new settlement. Some of the people who joined Nwoko in his new outpost include: Omezi, Obodo, Obu, Iyitor, Ina, Osei, Ekwulu, Oko-Onyeme, Mokobia, Osigwe, Igha, Okohue, Biachi, Nwonye, Agwaibor, Bamah, Edemodu, Nwulu, Oghedo and Esonye. Onaifo’s children, Agbodu, Nwa-Agaheze, Onyeoba, Odor, Ebene Ataah, Aligbe and Nwoko’s mother Moise also joined him. One person who did not join Nwoko in his new farm settlement was his younger brother Igbenabor who stayed behind in Idumuje-Unor.

In spite of the perceived ‘injustice’, Nwoko continued to pay homage to the Obi of Idumuje-Unor. The homage was mostly hunted wildlife largess. At some point, Obi Anyasi became apprehensive receiving and consuming Nwoko’s hunted wildlife. Prompted by his wife, he refused to accept Nwoko’s gifts, believing that he could be poisoned. Instead, he told Nwoko that he will cease to accept his gift. He chided and labeled him and his fellow farm settlers ‘primitive’ people. He urged him to kill and consume his hunted wildlife. During one of his homages to Idumuje-Unor, Obi Anyasi covered Nwoko in the traditional white chalk, a sign that bestowed on him the leadership of the new settlement. This new settlement was initially called Idumuje-Ugbo-Nwoko.

As the fledgling community began to take shape, the Nwoko family, through Nwoko I emerged as the royal family. Since its inception, six generations of the Nwoko dynasty have continuously ruled Idumuje-Ugboko. The six generations are: HRH Obi Nwoko I; HRH Obi Amoje; HRH Obi Omorhusi; HRH Obi Justine Nkeze Nwoko II; HRH Obi Albert Nwoko III, and HRH Obi Nonso Nwoko, the incumbent Obi.

Nonetheless, in 2001, some historians inaccurately claimed that Idumuje-Ugboko was founded by Nwoko I between 1672 and 1677. Using reverse chronology – the act of recalling historical events in a reverse date order, they calculated the ages of each monarch, as well as the supposed year of death. They also, where possible, calculated how long each of them ruled. They stated:

- Obi Albert Nwoko III was born in 1926. In 2001 he was 75 years old.

- Obi Justine Nkeze Nwoko II was 64 when he died in 1955

- Obi Omorhusi died at 90.

- Amoje reigned for just six months. He died at 45

- Nwoko I lived for 95 years

Together, these parameters gave them a cumulative figure of 369 years – made up of the longevity of each monarch – from Nwoko III to Nwoko I. They proceeded to deduct the 369 years from the year 2001 and arrived in 1632. With this guide year, they concluded, albeit wrongly that Idumuje-Ugboko was founded between 1672 and 1677, citing 1677 as the most likely date.

Understandably, some historians (including the authors of this work) vehemently dispute and remain unconvinced about the accuracy of these dates but not necessarily the methodology used. To begin to disprove the validity of this date, we will juxtapose and critically examine the timelines of the five generations of the Nwoko dynasty with some of these newly discovered materials from the archives of the Church Missionary Society (C.M.S.).

HRH Obi Albert Nwoko III

Obi Albert Nwoko III was born in 1926. He ascended the throne in 1955 but was crowned in 1981. Technically, he ruled for 36 years. He was 91 years old when he died on 6th February 2017

HRH Obi Nkeze Nwoko II

Contrary to the widely circulated date, Obi Nkeze was born in 1895 and not 1891. He ascended the throne in 1928 and ruled for 27 years. At the time of his death in 1955, Nkeze was 60 years and not 64 years old.

HRH Obi Omorhusi I

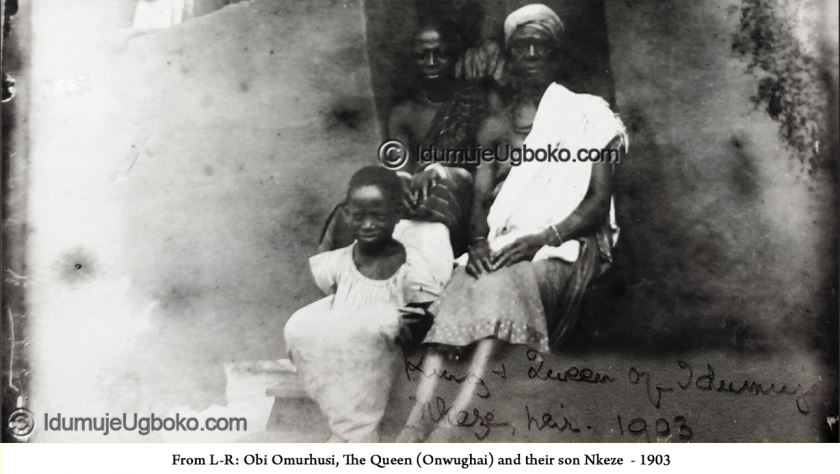

Without the safety net of a birth record or any other form of documentation, it is difficult to state the exact year Omorhusi was born. Nonetheless, working back from the year he died, it is possible to determine how long he lived, and by implication, his likely year of birth. For a start, it has been validated that Omorhusi died on January 23, 1928. The next big question is, when was he born? To help answer the question, three leads will be explored, a) the corroborated account of his burial and the subsequent installation of his son Nkeze, b) the ‘partial’ birth record of Nkezi, c) a detailed look at Omorhusi’s 1903 C.M.S. picture.

According to Idumuje-Ugboko tradition, the death of the Obi, the burial, and the installation of a successor usually happen instantaneously. In the palace records, it was clearly stated that following the death of his father on Monday, January 23, 1928, Nkeze was immediately installed. This incontrovertibly establishes one fact – that there was no interregnum between Omorhusi’s passing and Nkeze becoming the next Obi. In other words, following the passing of his father, Nkeze immediately assumed the position of the Obi of Idumuje-Ugboko in 1928.

On his likely year of birth, two very significant information in the Niger Dawn comes in handy. First, according to Frances Hensley, Nkeze was 7 years old in 1902. Second, Omorhusi was described as ‘a simple youth’. According to the United Nation’s definition, the age range of youth is loosely between 15 and 24 years. So, if he was a youth in 1902, this implies that Omorhusi could have been between 15 and 24 years old. When you subtract 1902 from 1928 (the year he died), it shows a difference of 26 years. This is significant because the difference is roughly in line with the universally acclaimed definition of a youth, be it, in this instance, just 2 years over the upper threshold. If we assume that he was 26 in 1902, a count back will point to circa, 1876 as his likely year of birth. Nevertheless, should we decide to err on the side of caution and push back his birth year by 10 years to 1866, this will firmly put his age in 1902 in the unlikely bracket of 36 years. Why make the assertion that this is highly unlikely? The third clue – the C.M.S. picture – will shed more light.

In 1903, Frances Hensley took a picture of Omorhusi, his wife (Onwughai), and Nkeze, the heir to the throne. A closer examination of the C.M.S. picture clearly shows the physiognomy of a youth who could not have been 36 years. Putting aside this piece of evidence, let us apply simple logic. If Omorhusi lived up to 90 years as claimed, and considering that he died in 1928, working back from his year of death, this will put his birth year circa, 1838. If this date is assumed to be true, it means that in the 1903 C.M.S. picture, Omorhusi was 65 years old. Similarly, it also follows that he was 57 years old in 1895, the year Nkeze was born. From the above analysis, it is clear that both assumptions are inherently wrong because the newly discovered photograph cannot and does not support either claims. Sweeping together these anecdotal pieces of evidence, we came to the following conclusions:

a) Obi Omorhusi was born circa, 1876

b) following Amoje’s death he ascended the throne circa, 1893

c) he was aged around 17 years when he took the reins of power

d) Obi Omorhusi ruled for about 35 years

e) he died in 1928, aged 52 years.

Click here to read about The Impact Of The C.M.S. On The History Of Idumuje-Ugboko

HRH Obi Amoje

It is claimed that Omorhusi’s father, Amoje (who, from recently unearthed historical records may have been crowned Amoje Nwoko 1 – not to be confused with Nwoko – the founding father of Idumuje-Ugboko) was born, circa 1845. He ascended the throne between 1890 and 1892. He died circa 1893, aged 48.

HRH Obi Nwoko

Without the benefit of a written record, it is extremely difficult to work out Nwoko’s date of birth, the year he came to the present-day Idumuje-Ugboko, the year he ascended the throne and how old he was when he died. However, given that Nwoko unsuccessfully tried to claim the Odogwu title in Idumuje-Unor, it is unlikely this event took place during Nwoko’s teenage years. If this was the case as suspected, we came to the following conclusions: a) Nwoko must have moved to his farming outpost in his mid-twenties, b) the likely period he may have settled in the present-day Idumuje-Ugboko would be in the 1850s, c) with this guide year, Nwoko’s date of birth was likely to be in the 1820s, d) he must have died between 1890 and 1892, aged circa, 70 years.

Based on the timeline below, it is fair to conclude that Idumuje-Ugboko is far younger than many people believe or want to believe.

The Founding of Idumuje-Ugboko – Other Narratives

It has been arguably established that the founding of Idumuje-Ugboko is entwined with Nwoko I. However, there are two lesser-known but equally credible oral accounts about the founding of Idumuje-Ugboko. The two accounts are the Owo and the Emu Narratives.

The Owo Narrative

According to this account, a failed bid for the kingship stool in Owo, a town in the present-day Ondo State, incentivised the ancestors of Omezi to migrate via Issele-Uku to a sparsely populated Idumuje-Unor. On arrival, they settled in a section of the town called Ime Ogbe Isagbeme, a predominantly migrant quarter. This period in Idumuje-Unor was punctuated by incessant invasions from neighbouring towns and villages. Considered seasoned warriors, the new arrivals were tasked with repelling the invaders. The migrants learned from their host that the attacks were mainly carried out by people from the nearby towns of Issele-Ukwu, Onicha-Ugbo and Obior. A plan was hatched to embed and split the newcomers into three different villages to act as the first line of defence. With the passage of time, the strategy paid off. It stemmed the frequency of the attacks and completely stopped the invasions. This brought relative peace and safety to the community.

Many generations later, Omezi was born. When he came of age, he moved further afield, acquiring swathes of agricultural farmland which he cultivated using his numerous serfs. This earned him enormous wealth, success, recognition and clout. For economic reasons, Omezi decided to permanently leave Idumuje-Unor to a location in one of his numerous farms. He followed the legendary and well-trod migratory route from Idumuje-Unor called the Akoroko or Apuloko road. The Akoroko road is named after a revered tree. Many years later, this important tree was felled by Tata from the Olomina family and sold as timber in Sapele. The new location was originally called Igbo Oko which in the Yoruba language means ‘a farm in a forest’. The name according to this narrative was later anglicised to Ugboko. Omezi settled in one of his Egbenu (small) farms in Idumu Ina in the present-day Atuma village. Shortly after, other migrants from Akpo or Epkon, Onije, Ikoko and Emu or Emule also arrived. Prominent among the early arrivals were the ancestors of the present-day Ogbe-Ofu village.

When the Odogwu position became vacant in Idumuje-Unor, Omezi nominated Nwoko (whose name originally was Nwadiukor or its shortened version Nwokor) to succeed his father as the Odogwu. Unfortunately, Nwoko failed to garner enough local support and subsequently lost the position to his younger brother, Igbenabor. Omezi displayed a commendable sense of empathy by offering Nwoko refuge in his new settlement. He used his serfs to erect a house in one of his farm settlements for Nwoko and his family. When the need for a king arose in Idumuje-Ugboko, the natives wanted Omezi or Mokobia, a very powerful seer and the first free-born to settle in Idumuje-Ugboko to be their ruler. Both refused. On his part, Omezi specifically cited the need to concentrate on his farm. A testament to this resolute commitment was the naming of one of his sons (Gabriel Omezi) Ugbomkanmai, meaning ‘it is my farm I know or care about’. On the other hand, Mokobia who was qualified for the position was too old and blind.

As the de facto kingmaker, Omezi’s intention was to replicate the Owo kingship system in Idumuje-Ugboko. The system was anchored on the handpicking of potential candidates from the same lineage but not necessarily from the same nuclear family. The selected candidates were subsequently whittled down until the Obi is selected. It was this system that enabled Nwoko to emerge as the first leader, or more appropriately, the first Odogwu of this new settlement.

When Nwoko died and at the behest of Omezi, his son Amoje, was nominated to succeed him. Following the death of Amoje, Omezi also nominated Omorhusi, Amoje’s first son as the next king. The death of Omezi circa, 1914 paved the way for Nkeze to succeed his father, Omorhusi. It is claimed that this particular succession was done in connivance with the British colonial government. This ran contrary to Omezi’s initial plan of instituting and maintaining a nonhereditary monarchy in Idumuje-Ugboko. The enthronement of Nkezi inadvertently legitimised and irreversibly ‘foisted’ a hereditary monarchy on the nascent town of Idumuje-Ugboko – a development that continues to rankle and displease some descendants of the early settlers up to this day.

The Emu Narrative

This narrative states that an unsuccessful struggle for the chieftain in Emu or Emule, a town in the present-day Edo State, forced the departure of a group of migrants, first, to Idumuje-Unor and then Idumuje-Ugboko. The most prominent of the migrants was Unoko who settled and died in Idumuje-Unor. However, it was one of his descendants Agwai and other emigres who eventually made it to Idumuje-Ugboko. On arrival, the migrants settled in the present-day Ogbe–Ofu village. In no time, the immigrants recognised that they were tenants on the land that belonged to the Idumuje-Unor kingdom. The tenancy status compelled them to pay regular homage to the Obi of Idumuje-Unor. Once ‘securely’ settled in their new environment, the migrants decided to replicate the various structures of government they imported from Emu. They formed an autonomous community, complete with a traditional ruler and chiefs. Nonetheless, finding themselves in the throes of instability brought about by the never-ending inter-tribal wars and invasions, the Ogbe-Ofus saw the need to join forces with other neighbouring settlements. A sustained period of contact fast-tracked the coalescing of previously isolated and outlying settlements into a homogeneous group. The coming together inevitably threw up a challenge – who should be the king? Mokobia, a competent and perfect fit for the position was not only old, but he was blind as well.

Even though they recognised the need for a chieftain, the Ogbe-Ofus had other motivations for desiring one. Curiously, they downplayed the position of the Obi. They regarded it as unimportant. Instead, the Ogbe-Ofus coveted the Odogwu and the chief priest positions. To get the desired positions, the Ogbe-Ofus reached a negotiated settlement with the other farming outposts. This resulted in the Ogbe-Ofus voluntarily ceding the position of the Obi but appropriated the Odogwu and the chief priest positions. This cleared the way for the Ogbe-Obi village through the Nwoko family to claim the Obi, while the Iyase position went to the Atuma village.

Irrespective of the narrative you are minded to believe, the authors strongly believe that the present-day Idumuje-Ugboko was originally an unclaimed, ‘no-man’s land’ forest reserve, used mainly by itinerant farmers, whose permanent homes were initially removed from the reserve. At irregular intervals, some of these itinerant farmers started to stay longer on their farms but paid little attention to the other settlements around them. This gave each outpost the erroneous impression that they were the first to arrive at this forest reserve. As these distinct settlements started making ‘sustained contact’, they realised the need to band together, seeking common grounds of cooperation, especially on security, as the period was scarred by internecine wars, the slave trade, and unending invasions. The pooling together of both human and agricultural resource laid the foundation for the emergence of a structured, homogeneous community, culminating in the founding of the present-day Idumuje-Ugboko.

The Etymology Of The Words ‘Idumuje-Ugboko’

Historians agree that the name Idumuje-Ugboko is a composite word, derived from two distinct words, Idumuje and Ugboko, but are hopelessly at odds with one another on how the name came about. According to the various oral accounts, there seems to be a convoluted relationship between the name of the town and the identities of the presumed founder (s). One striking relationship links the name of the community to the presumed founder – Nwoko, hence, the settlement was initially called – Idumuje -Ugbo-Nwoko. But how did Ugbo Nwoko (Nwoko’s farm) become the eponym for Idumuje-Ugboko?

A feasible, yet simplistic explanation may be found in the interpretation of the words Idumu and Ugboko. It could be that once the occupants of this new farm (Ugbo) settlement bonded together into a close-knit community, they may have seen themselves as settlers on a farm settlement that was founded by Nwoko. As a result, they may have decided to identify themselves as Ndi-Ugbo-Nwoko, meaning ‘natives of a farm owned by Nwoko’. Also, the meanings of the words Idumu and Ugboko may further shed light on how the name came about. It could be that the settlers initially regarded the settlement as an ‘autonomous’ Idumu or quarter. In order to distinguish this quarter from other ‘rival’ quarters, they may have added the word Ugboko, meaning ‘thick forest’. The joining of the words Idumu and Ugboko could be a well-meaning initiative to distinguish this monolithic Idumu from the other nearby Idumus that happen to be in the same thick forest. Hence the name, Idumu-Ugbo-Nwoko.

In spite of the various blends of sophistries, the authors strongly believe that the ancestral link to Idumuje-Unor and the need to preserve this kinship offers a more persuasive explanation on how the name came about. As the new settlers contemplated a new name for the new settlement, it made sense to ‘borrow’ the word Idumuje from the town they just migrated from. Consequently, to help identify this new settlement as a separate, and quite possibly, an ‘autonomous community’, they may have decided to add the word Ugboko‘, thereby forming the composite name – Idumuje-Ugboko. This plausible theory renders redundant the emotive argument that the name Idumuje-Ugboko was either derived from a farm settlement that was founded by Nwoko – Ugbo Nwoko, ‘Nwoko’s farm’; or that the name was originally Igbo Oko – ‘a farm in a forest’. Yes, Nwoko may have been the first to settle on this farming outpost and his presence may have acted as the ‘magnet’ for other settlers. However, this alone does not answer many questions thrown up by this assumption. Consequently, it will amount to excessive sentimentality not to see the eponym for what it is – a possibility rather than a certainty.

The Constituent Parts Of Idumuje -Ugboko – (The Village, The Ebo And The Quarter)

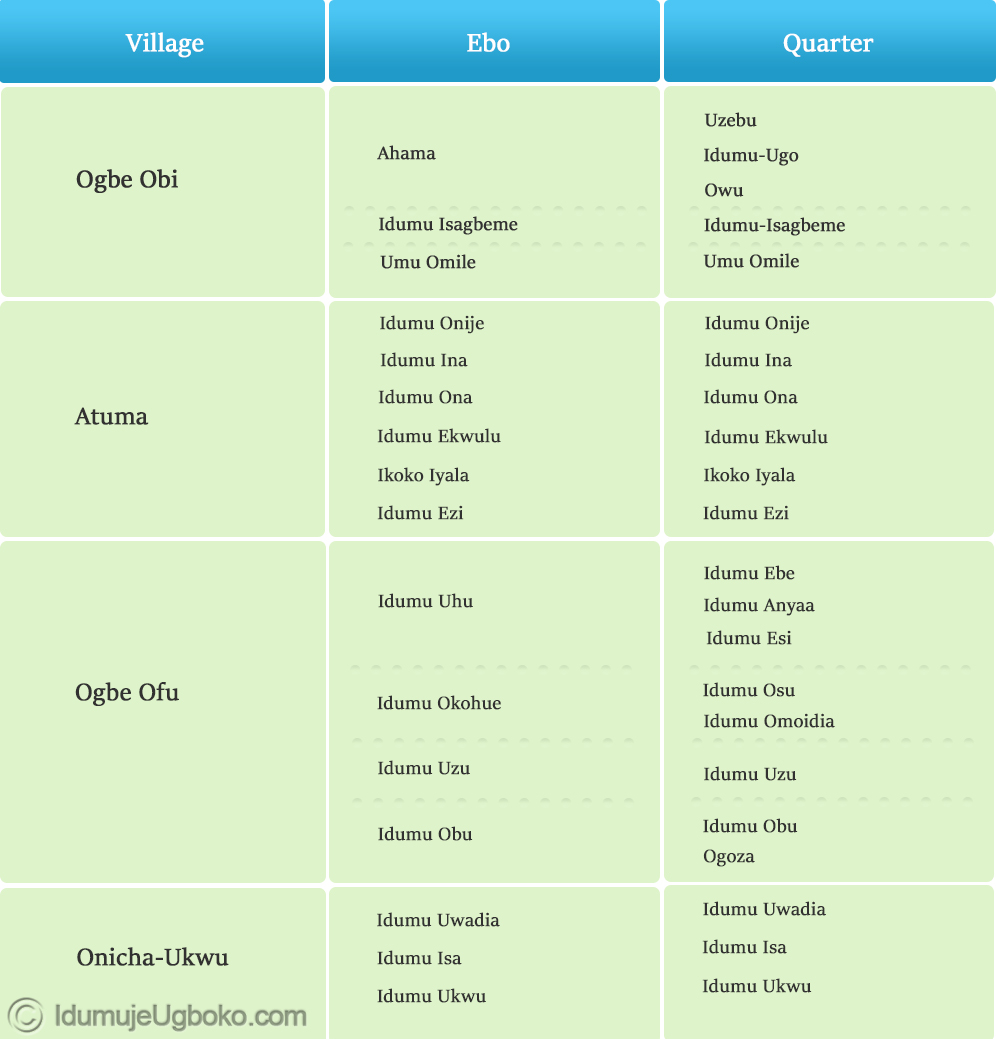

Idumuje-Ugboko is made up of inexactly four villages. What arguably could have counted as the fifth village, Ani-Ofu will be dealt with separately. The four villages are:

- Ogbe-Obi (the village of the monarch)

- Atuma

- Ogbe-Ofu

- Onicha-Ukwu (Ogbe-Akwu)

A further segmentation shows that the constituent villages are made up of approximately sixteen Ebos and twenty-three Quarters widely known as Idumu. It is worth bearing in mind that the naming system and the characteristics of the Ebo and the quarter (Idumu) can sometimes overlap. Nonetheless, this peculiarity does not diminish their uniqueness.

The Line Of Descent Of the Various Ebo Units Of Idumuje-Ugboko

According to A Combs & Coombs Resource for Researchers, a line of descent is the order of succession of blood relatives from their common ancestors. Such descent can either be Lineal or Collateral. Lineal descent is a direct line of descent, e.g. from parent to child, while a collateral descent is an indirect form of descent, e.g. traced initially to one ancestor before branching out from brother to brother, uncle to nephew, etc. In Idumuje-Ugboko, the line of descent of the various Ebo unit is collateral.

The Ebo units and the quarters that make up the four villages trace their ancestry to nearby towns and villages, and sometimes, some obscure royal houses. For example, but in no particular order, the Umu Omile of Ogbe Obi village trace their origin to Idumu Obu in Idumuje-Unor; Idumu Ona of Atuma village claim an ancestral link to Amafor, a town in the present-day Edo State; Idumu Anya of Ogbe-Ofu are reputed to have migrated from Emu, a town in Edo State, while Idumu Ukwu of Onicha-Ukwu trace their ancestry to Owezim in Akure.

Ogbe-Obi

Ahama

Ahama is a town just outside Ubulu-Unor in Delta state. It is believed that the ancestors of Nwoko initially settled here after migrating from the Benin Kingdom. When they left Ahama, they briefly stayed at Obior before moving to Idumuje-Unor. At the end of their sojourn in Idumuje-Unor, Nwoko, his mother, brothers, wives, and children eventually settled in the present-day Idumuje-Ugboko. It is worth pointing out that the people of Owu quarter are direct descendants of Aluya, while the Uzebus are descendants of Onaifo. Idumu-Ugo trace their lineage to Ahama in Ugbodu. The Ebo Ahama trace back their root to Onaifo through Nwoko and the royal household. Of all the Ebos, Ebo Ahama has the longest bloodline.

Note:

Following the destruction by fire of the highly revered Ofor Ebo (the staff of authority) in the 1980s, a replacement Ofor Ebo was presented to the Idumuje-Ugboko Ahamas by the eldest Ahama from Ahama. During the ceremony, the marriage restriction between the Aluya lineage (Owu quarter) and the descendants of Onaifo (Uzebu quarter) was lifted. Despite the loosening of the constraints, the two quarters still maintain the longstanding tradition of not contracting marriages between the two groups.

Idumu Isagbeme

The ancestors of the Isagbemes followed the same migratory path as Nwoko – see Ahama above. Their descendants include Mokobia, Okoh, Osemeke, Vincent, Obodo, Dibie, Akata, Oba, Asia, Agbor and Jide.

Umu Omile

The Omiles originally came from Idumu Obu in Idumuje-Unor and settled in Ogbe-Obi village.

Atuma

Onije

The Onijes are the direct descendants of Isi, who originally came from Onije, a town in the present-day Ika Local Government Area of Delta State. Ogbechie, Osajei, Egbunowor, Nkeaniekwu, and Diai are direct descendants of Isi.

Idumu Ona

The Idumu Ona trace their ancestry to Amafor in Edo State. First, they migrated to Onicha Ukwu, then Ubulubu before finally settling in Idumuje-Ugboko. The descendants of Ona are Nwaeze and Awolo.

Idumu Ina

Idumu Ina ancestors are believed to have originally come from Ikoko and Ogho Owo in present-day Ondo State. Their early movements can be traced back to Benin from where they moved to Idumuje-Unor before making Idumuje-Ugboko their final destination. Ugbo, Egbo, Ilo, Osu, Omezi, Akpe, Chiekwene, Nwani and Mgboli trace their ancestry to the unnamed man that left Owo.

Ikoko Iyala

Uselu-Oba in Benin city is reputed to be the ancestral home of the Ikoko Iyala Ebo. Legend has it that they left Uselu due to tribal war. Egbe, Anea, Okafor, and Uwagu are the descendants of Ahomose from Uselu-Oba.

Idumu Ezi

Ayomo, the forebear of Idumu Ezi migrated from Benin to Idumuje-Unor. His descendants are Anyansi and Elumelu.

Idumu Ekwulu

Idumu Ekwulu derived its name from Ekwulu, the only daughter of Ikoko who, it is claimed, migrated from Owo in the present-day Ondo State. For unknown reasons, Ikoko, Ekwulu’s father barred her from marrying. Instead, she was ‘kept at home’ to procreate – a classic case of Androcentrism. Echinne, Ugbwa, Ezeabor, Usifo, Nwogogo, Ogboe, Igbedor, Nwogu are ancestors of the Idumu Ekwulu.

Ogbe-Ofu

Idumu Anya

The ancestors of Idumu Anya came from Emu in Edo State. Following a misunderstanding, Agwai fled to Ukwu-Nzu before moving to Idumuje-Unor, and later to Onicha-Ugbo. He moved back to Idumuje-Unor and finally to Idumuje-Ugboko. Nwaenyi, Odu, Chinye, and Akamagwuna have direct links to him.

Idumu Okohue

Akure has been cited by historians as the likely origin of this Ebo. Temporarily moving to Benin, they migrated further East to Idumuje-Unor, before finally making it to Idumuje-Ugboko. Ayomor, Omoidia, Aligbe, Ukwu-nne, Ogboyi and Mgbakor are all children of Okohue.

Idumu Uzu

The word Uzu means blacksmith in the English language – the legacy of a group of people skilled in the use of iron to produce domestic and iron-based farming tools, as well as low-grade weapons. Ozigwe, a blacksmith migrated to Asaba from Akpu (Ekpon) before making his way to Idumuje-Ugboko.

Idumu Obu

The ancestors of the Idumu Obus are said to have originated from Umudaike quarters in Asaba, Delta State. Their ancestors, Uche and Nomor moved from Asaba to Idumuje-Ugboko, but not before a brief stay at Idumuje-Unor. Strangely, the Idumu-Obus have no Ebo head in Idumuje-Ugboko. Instead, the head of the Ebo is in Idumuje-Unor. Two lineages of Uche and Normor make up the Idumu Obus. The lineage of Uche includes; Uche, Ukwudomor, Osemede, Dibie, Edio, Osakwe and Obuzome. Monye, Umemezie, Onuwa, Okonkwo, and Okonji are from the Nomor lineage.

Ogozar

Owo is believed to be the ancestral home of the Ogozars. Their presence in Idumuje-Ugboko was precipitated by the habitual act of androcide. Their ancestors first moved to Igarra, then Ugbodu, before arriving at Idumuje-Ugboko.

At some point, Idumu Ogozar became subsumed into Idumu-Obu. This absorption took place during the reign of Monye as the head of the Ebo. The assimilation allowed the lifting of the marriage restriction between the Ogozars and the Idumu-Obus.

Onicha-Ukwu

Idumu Ukwu

Owezim, the ancestor of Idumu Ukwu migrated from Akure to Benin and then to Ukwu-Nzu where he settled. It was Eboka the son of Owezim who made the journey to Idumuje-Ugboko. Eboka’s sons are Okpa, Mmecheta, and Onyema.

Idumu Isa

Iduwebo Aweto, an Ishan speaking area in the present-day Edo State is the ancestral home of the Idumu Isa. According to oral account, Dibie left this area to further his skills as a native doctor. When he got to Idumuje-Ugboko he was tasked by Nwoko I to go and restore the sight of the Obi of Obior. He successfully restored his sight and the Obi gave Dibie a wife as a thank you gift. Dibie ‘triumphantly’ came back to Idumuje-Ugboko and was made the head of the Ebo of the Idumu Isa by Nwoko. The name of his son was Chiemeke.

Idumu Uwadia

Uwadia moved with his wife Azormo, from Benin to Igbodo where they initially settled. In the intervening years, they moved to Onicha-Ukwu, a town in the present-day Aniocha North Local Government Area of Delta State. The notoriety of one of his sons as a thief incurred a curse on the family. This led to the dispersal of the family unit. The unfortunate incident forced Uwadia’s sons, Kegwu and Agbor to move their families to the present-day Idumuje-Ugboko. Kegwu’s children are Osubor, Egbuchiem and Osaji.